Opera Omnia (2019)

Opera Omnia. Installation view.

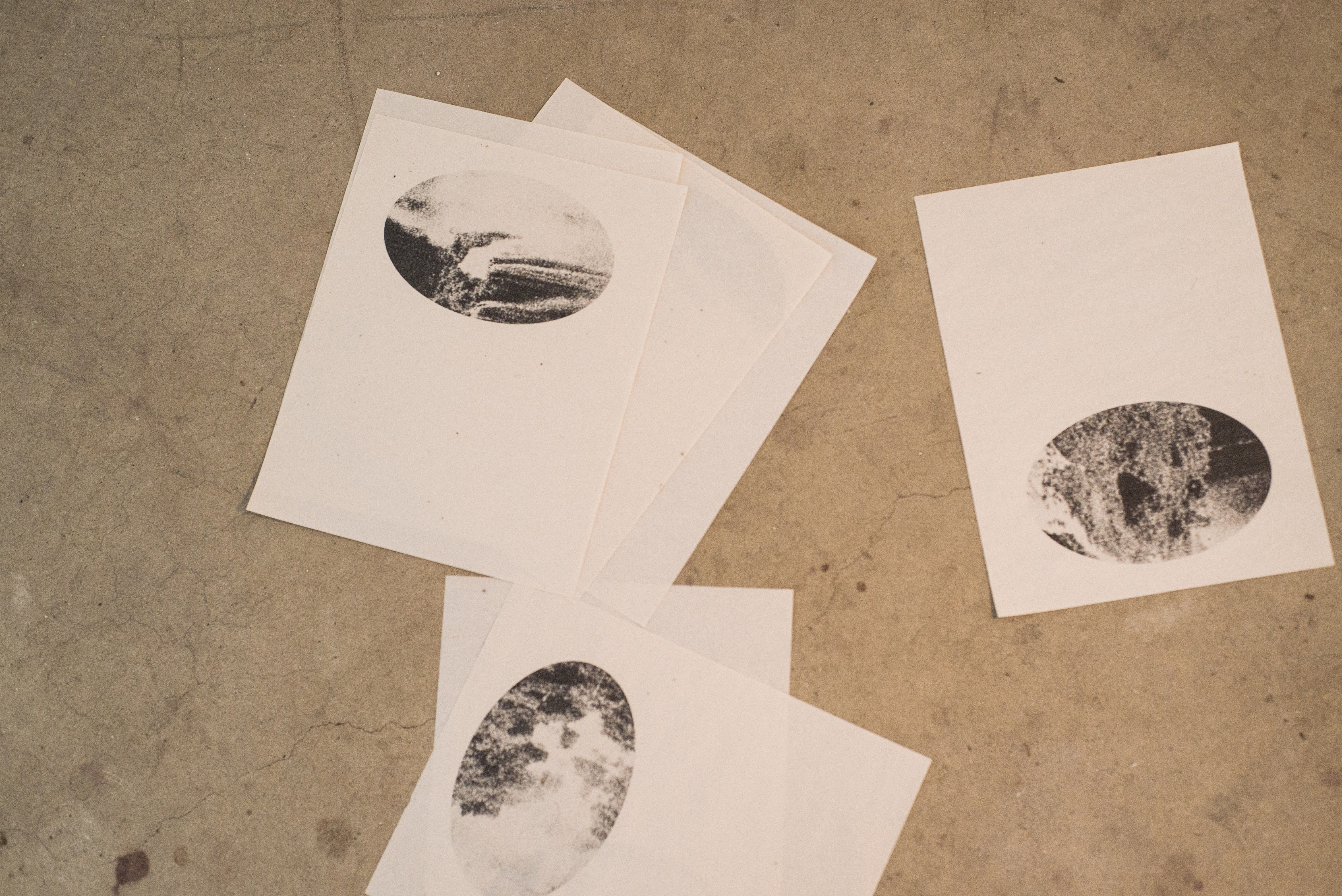

Marbleized Fragment, 500% (2019). Inkjet print.

Opera Omnia. Installation view.

Summa pornographica (2019). Gold-leafed pubic hair on jewelry box.

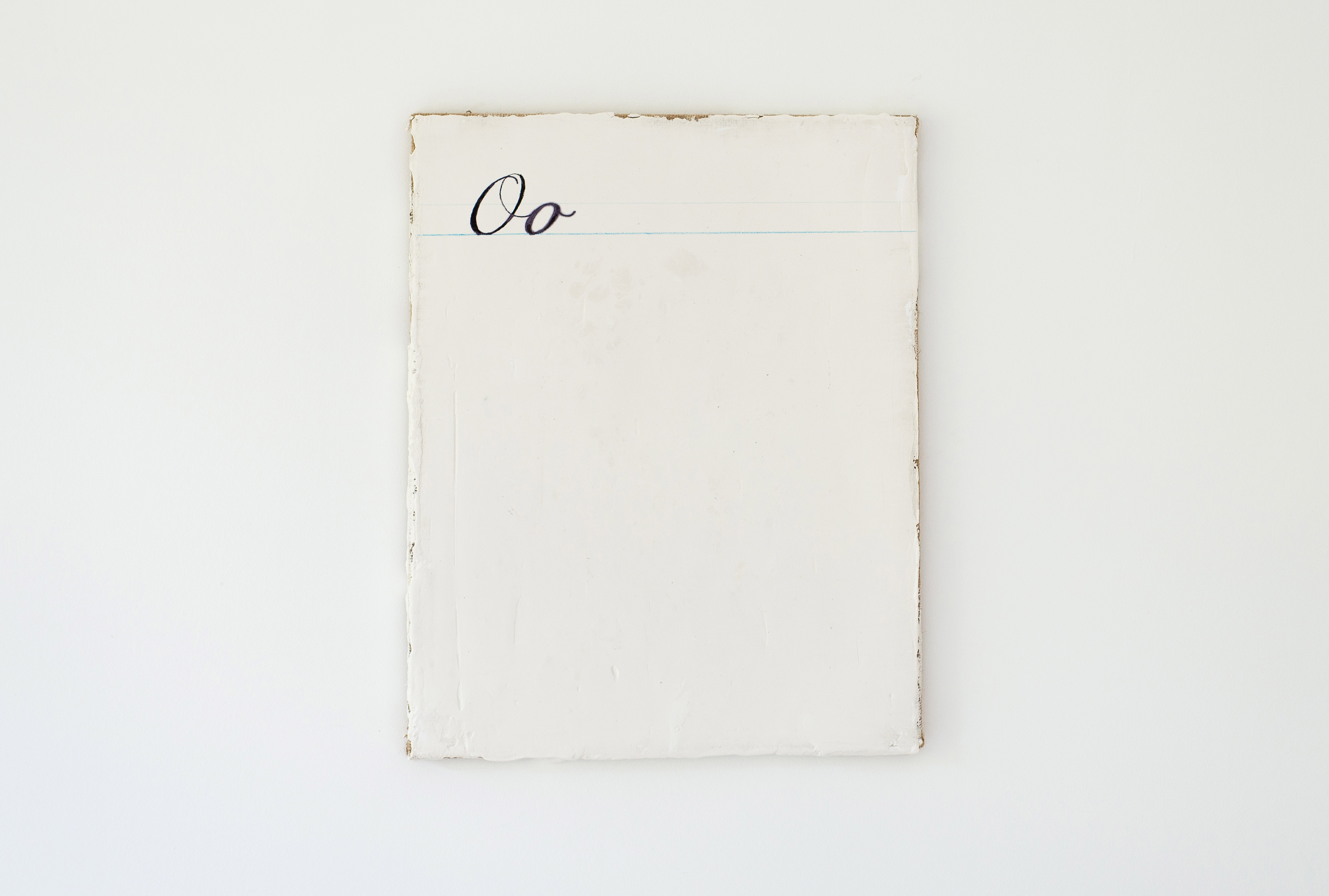

Writing Lesson (2019). Felt-tip marker and color pencil on plaster.

Opera Omnia. Installation view.

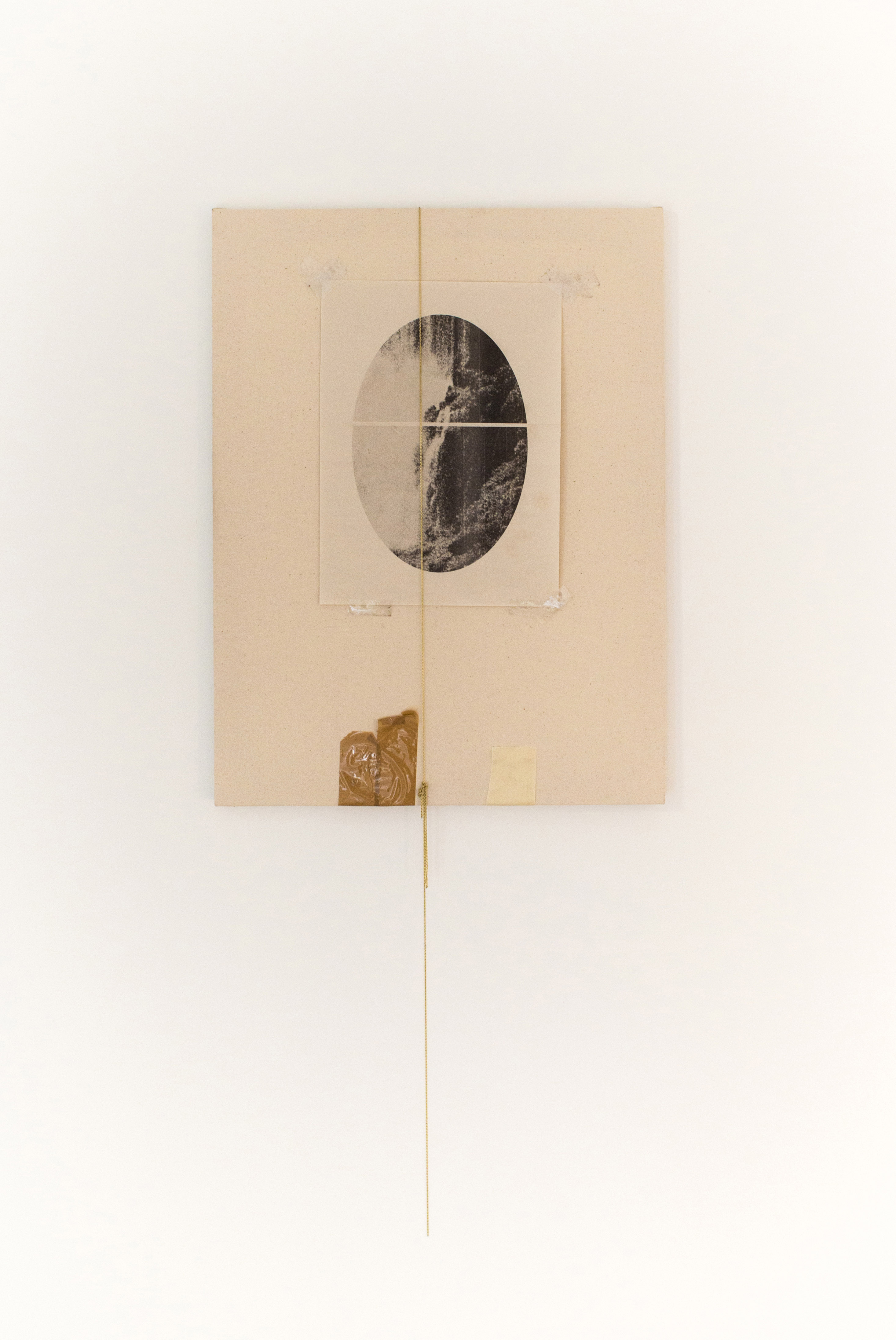

Opera Omnia, Vol. 1, Waterfalls, pp. 36-47 (Study for OOV1Wpp36-47.jpg) (2019). Toner and red marker on gray paper mounted on crushed velvet paper.

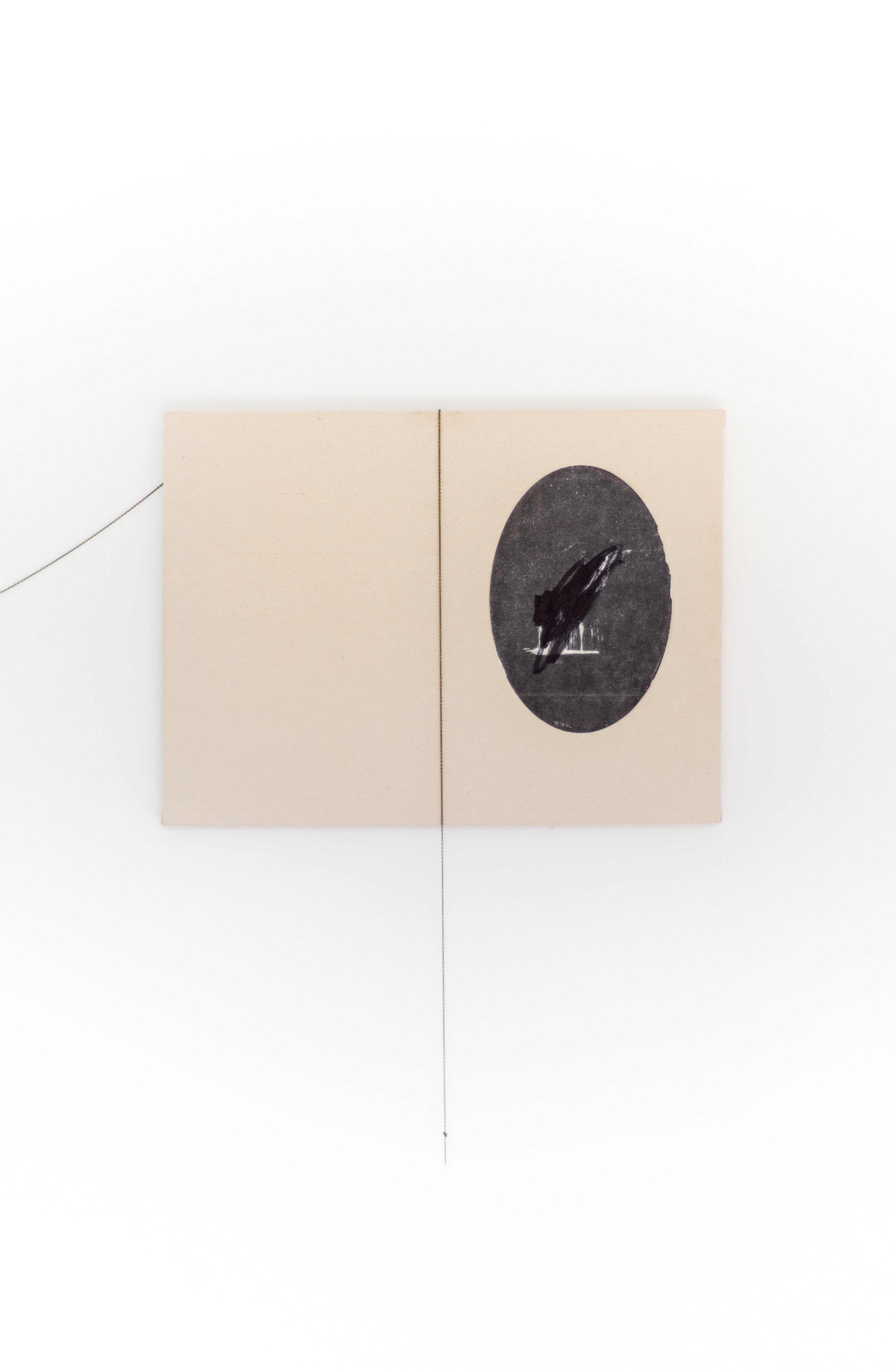

Opera Omnia, Vol. 1, Waterfalls, pp. 12-13, VERSO/RECTO (2019). Black marker, acrylic, toner, and bronze cable chain on raw canvas.

Opera Omnia. Installation view.

Opera Omnia, Vol. 1, Waterfalls, pp. 12-13, VERSO/RECTO (2019) (detail).

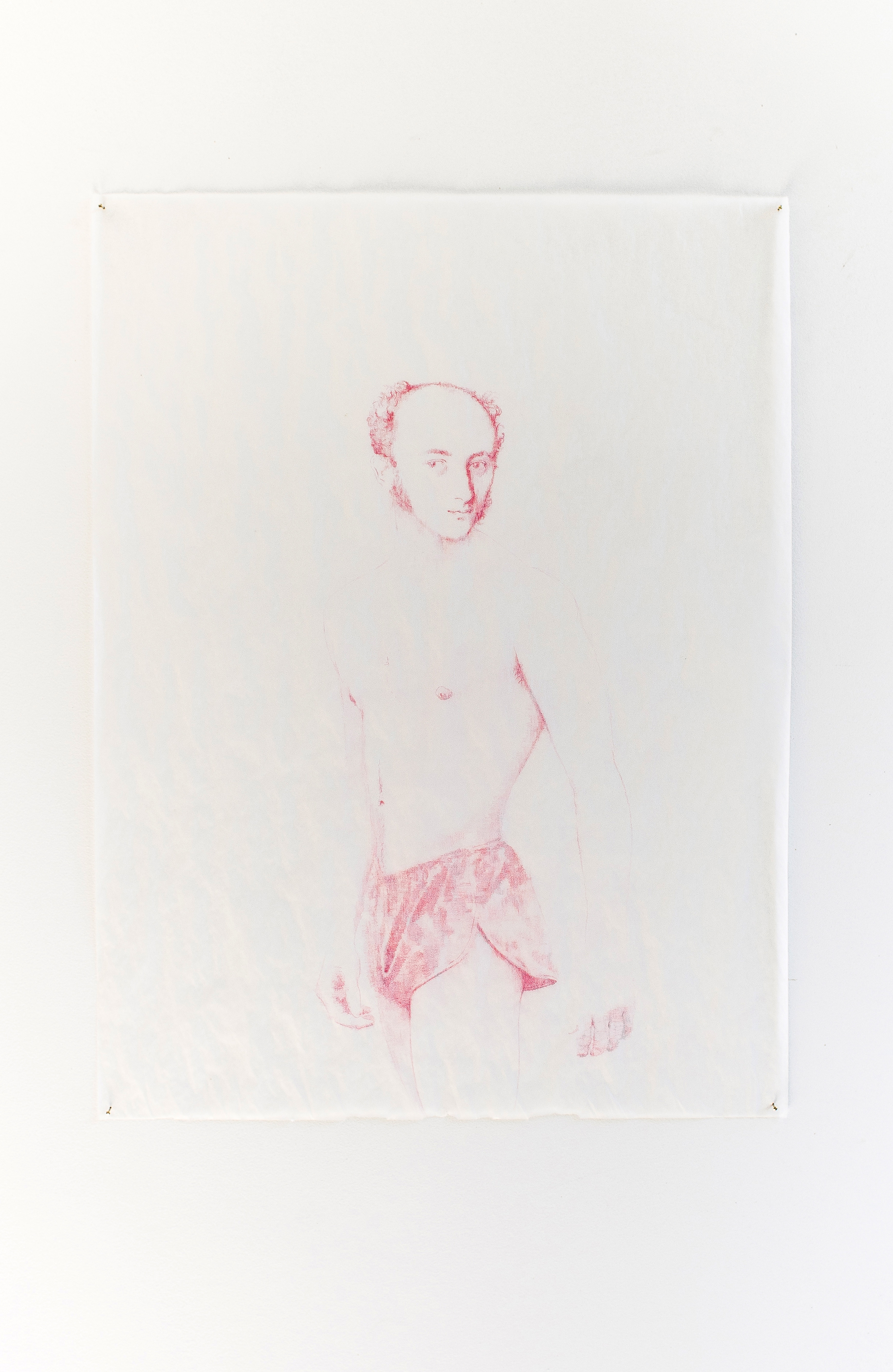

Study for a Chimera (Achille Leclere by Ingres [Naef, Die Bildniszeichnungen von J.-A.-D. Ingres, Cat. No. 89]) + International Male, Autumn 1991, French Chic, Activewear, Onionskins® Collection, p. 31 (2019). Red pencil on onion-skin paper.

The book should, by correspondences, institute a play of elements that confirms the fiction (2019). Packing tape, clear tape, masking tape, paper tape, gold and bronze cable chain, muslin, inkjet and toner prints on newsprint, custom-built lamp.

The book should, by correspondences, institute a play of elements that confirms the fiction (detail).

The book should, by correspondences, institute a play of elements that confirms the fiction (detail).

The book should, by correspondences, institute a play of elements that confirms the fiction (detail).

The book should, by correspondences, institute a play of elements that confirms the fiction (detail).

Opera Omnia

Opera Omnia, the title of Christopher van Ginhoven Rey’s exhibition, is a Latin phrase used to refer to an edition of a writer’s complete works. It’s a strange choice for a title, and maybe even something of a joke, as it is plainly at odds with what is on display in the exhibition space of The Tack Room: not just a very small number of works (too small, it would seem, to stand for someone’s total output) but also nothing that resembles what we have come to associate with a writer’s actual output. Pages scattered across the floor or arranged in a grid; a framed close-up of the marbleized paper that used to line the covers of bound volumes; empty surfaces bisected in ways that evoke the division between the verso and the recto sides of a page: if there is a book here—and the artist insists that there is—it exists only as a series of isolated fragments. It is nothing more, and nothing less, than an idea, an effect of the labyrinth of correspondences and reflections that van Ginhoven Rey has carefully constructed.

A framed panel resting at the center of the gallery’s main wall provides a point of entry into this labyrinth. Titled Opera Omnia, Vol. 1, Waterfalls, pp. 36-47 (Study for OOV1Wpp36-47.jpg), it consists of a grid showing what would appear to be a selection of six two-page spreads (corresponding to the numbers in the title) of an actual book. Mounted on a sheet of black crushed-velvet paper, the spreads present six tightly cropped oval-shaped sections of various images of waterfalls, collected by the artist over years of scouring the media collections discarded by libraries. The arrangement mimes the display of digitized books—and in fact, as the title suggests, the panel is part of the preparatory work for an image that will exist in JPEG form. In thus reversing the trajectory that a work is conventionally expected to follow—from a concept developed with the aid of digital tools to a concrete instantiation in the real world—the artist makes it clear that his interest is in the book as, first and foremost, something to be imagined.

At the same time, this emulation of digital space is a way for van Ginhoven Rey to establish a dialogue with reflections on the book from the more distant past, among them those by the French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé, whose interest in “the parallelism of pages” becomes a point of departure for other works in the exhibition. Thus, in Opera Omnia, Vol. 1, Waterfalls, pp. 12-13, VERSO/RECTO, a bronze cable chain draped over a canvas divides a rectangular surface into two parallel planes. The line traced by this chain will travel outside of the canvas and up and down the gallery’s main wall, before disappearing into a crack on the cement floor. It is possible to read this disappearance as a self-concious enactment of a pervasive concern with emptiness, already implicit in the oval frame that makes an appearance throughout the exhibition space. Morphologically related to the letter “O” traced with marker on a raw plaster surface in Writing Lesson (in imitation of the sheets used to teach children how to write in cursive script), the oval can be read as a kind of stand-in for a “zero,” and thus as a shape where the abstraction of language yields to the even more radical abstraction of number: an apt cipher, in short, for the process of rarefaction at work in the attempt to construct something that shall exist primarily as an idea.

In a text accompanying the exhibition, the artist speaks of this rarefaction in terms of a broader interest in the transformative power of absence. There is no parallelism without a gap in between, and as van Ginhoven Rey suggests, this kind of empty space is bound to introduce the risk of something strange and unexpected making its way into any system. In Opera omnia, an exhibition marked by a strong conceptual orientation, the role of this alterity would seem to fall to the vagaries of sexual (and specifically homosexual) fantasy. Or, even more to the point, to a form of homosexual fantasy that is entangled, in ways that are often humorous, in a network of explicit and implicit art-historical allusions. A gold-leafed strand of pubic hair nestled in a jewelry box (Summa pornographica) faces a delicate drawing, on a sheet onion-skin paper, that combines the body of a model for the Onionskins® brand of running shorts (found in a 1991 edition of the International Male clothing catalogue) with a face by Ingres. Together with the images of waterfalls printed cheaply on sheets of newsprint and with the light issuing from a lamp pieced together by the artist in a small room off of the main gallery, these intimations of a body and of sexual desire may invoke the name of Duchamp (who made work out of his own obsession with Ingres) and the enigmatic and sinister situation of his Étant donnés. Previous projects by van Ginhoven Rey have explored what he likes to refer to as the “citation compulsion.” In Opera Omnia, citations are like the fragments of a shattered mirror that the artist is intent on reconstructing, perhaps with the hope of being able to gaze at an unbroken image of his own fetishistic passions.

—Tatsuo Watanabe