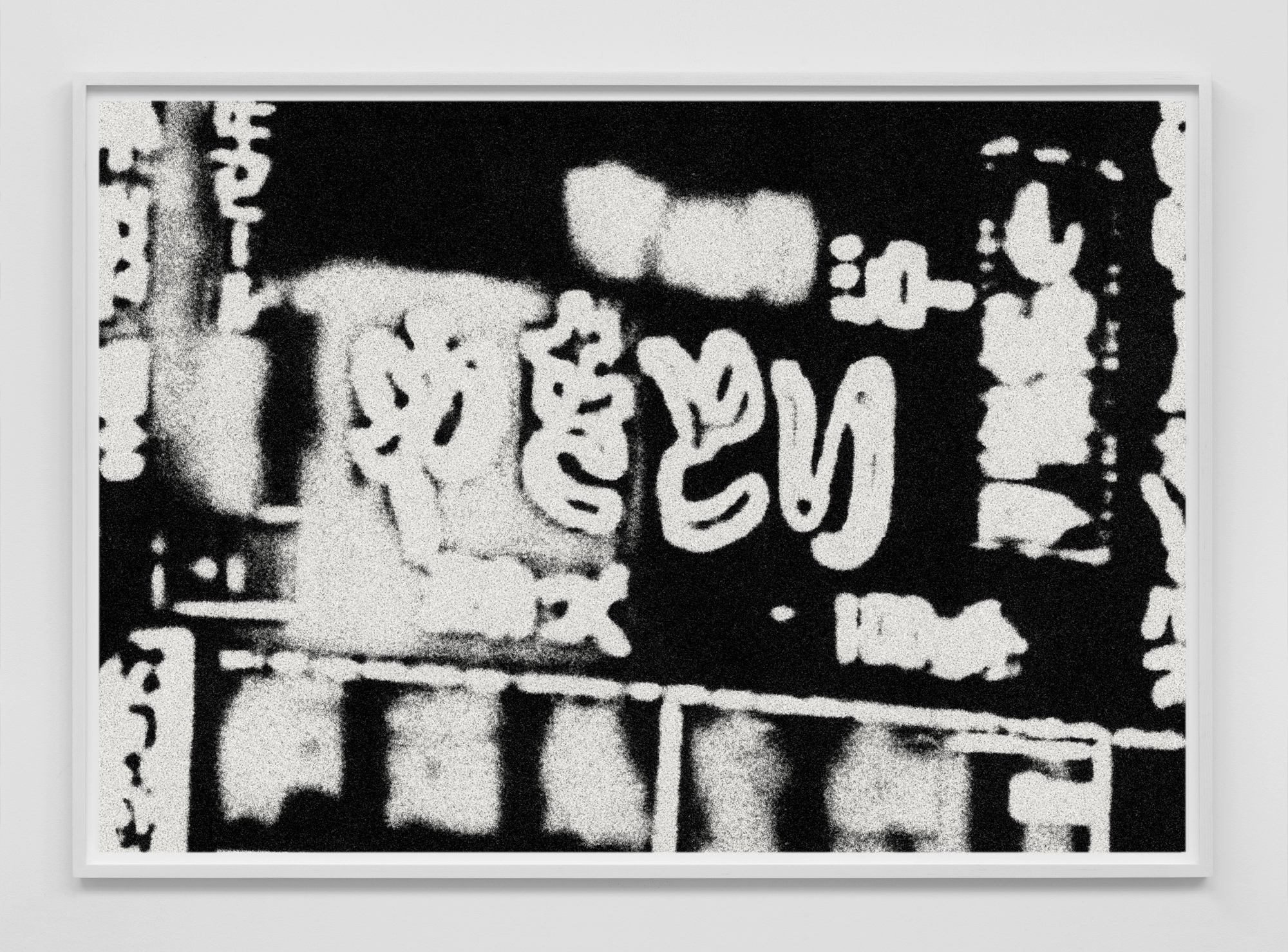

お雪 [001]

Inkjet print

28 x 20 inches

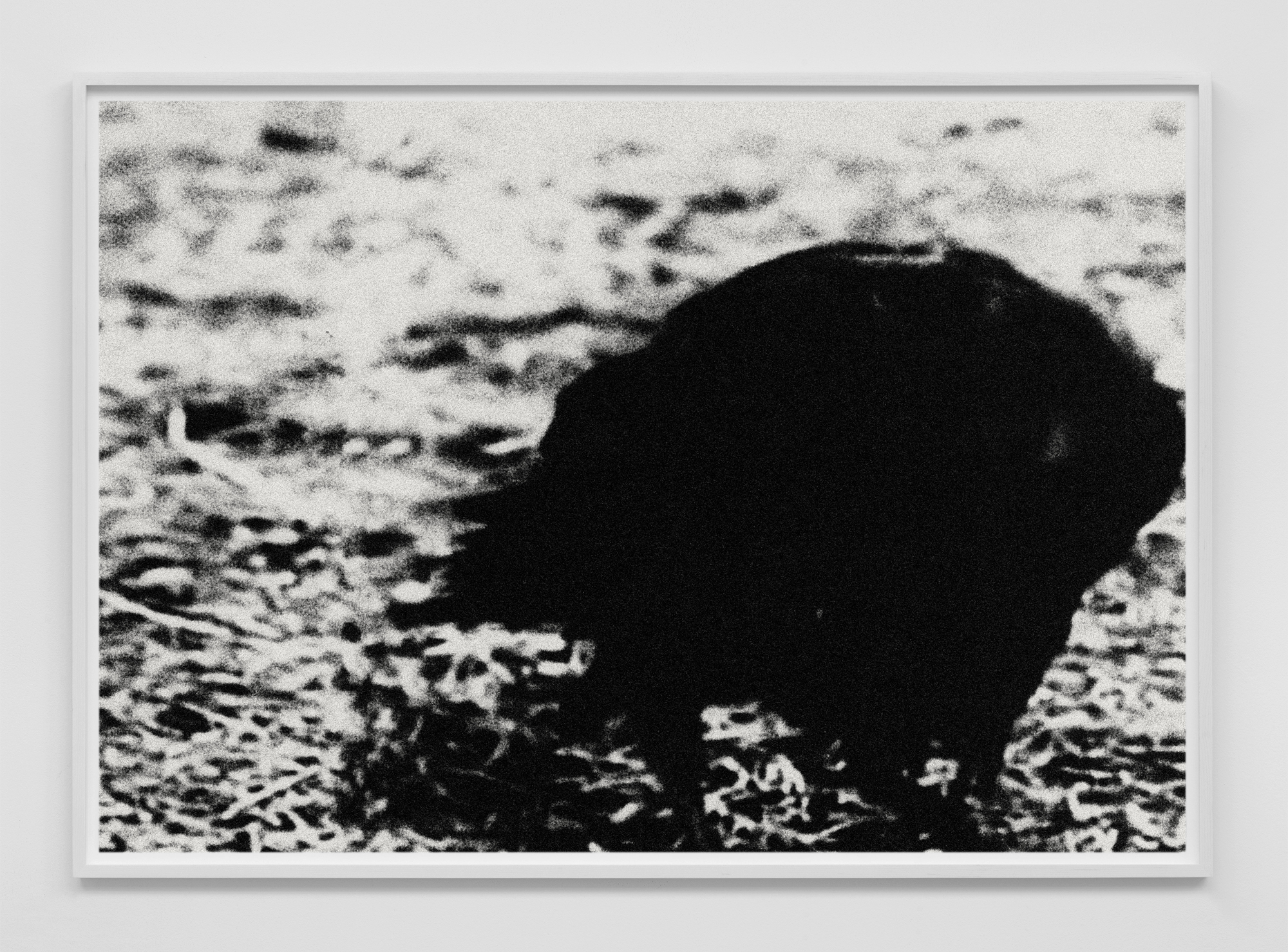

お雪 [027]

Inkjet print

28 x 20 inches

お雪 [013]

Inkjet print

28 x 20 inches

By the last few decades of the twentieth century, the Mexican conglomerate Televisa had come to dominate the media landscape of many Latin American countries. Peru, where I grew up, was no exception. Televisa was behind most of the foreign programming that did not originate in the United States, from children’s shows like El Chavo del Ocho to the soap operas aimed at adult audiences.

El pecado de Oyuki (Oyuki’s Sin) stands out among the latter. The story centers on Oyuki Ogino, a young Japanese woman whose brother takes her with him to Tokyo and forces her to work as a geisha to pay off his gambling debts. Among the audience during one of her performances one night is a young man by the name of Irving Pointer, the son of the British ambassador to Japan. A painter, Irving asks Oyuki to pose for a portrait in his studio. They quickly fall in love, to the displeasure of Oyuki’s brother, who is intent on marrying Oyuki to a wealthy Japanese executive. Oyuki escapes and marries Irving, and together they have a daughter, but eventually Oyuki’s brother finds them and kills Irving. Oyuki is blamed for her husband’s murder and ends up in prison, from where she is released fifteen years later, at which point she travels to England for an emotional reunion with her estranged daughter.

As a young boy I was not allowed to watch soap operas, but every night I managed to sneak out and join my grandmother, who at that time was living with us and who would not miss an episode of Oyuki’s story. Sneaking out like that was something I had done before, for other soap operas, but El pecado de Oyuki was unlike anything I (or anyone else, for that matter) had ever seen. It was an elaborate and expensive production, certainly by the standards of the time. Televisa’s set designers had built replicas of a temple and of several streets from the Ginza district in Tokyo on the foothills of an extinct volcano in the Ajusco, a mountain range south of Mexico City. Wigs, kimonos, and fans were imported from Japan, makeup artists and dance teachers were flown in, and a Mexican crew traveled to Tokyo to shoot footage of the city’s streets at night. It’s an important chapter in the history of the soap opera genre in Latin America, and in the still unwritten history of Orientalism in the region.

It’s been more than thirty since the final episode aired, but I still remember it vividly. Not long ago, I decided to watch the whole thing again, pausing to photograph the screen as I went along. I approached these sessions as an experiment, at once alchemical and philological. I was returning to a stream of images that had made a profound impression on me, and I was doing so with the express intention of transforming it into something else. I wanted to produce, out of each individual image, a different image, to alienate each image from itself. At the same time, I wanted also to produce a redundancy. I was not, in short, after a ‘new’ image. The aim of the photographic capture was not to release an unforeseen possibility, an image unlike any image anyone else might have seen before, and which I could therefore claim as ‘mine.’ If I say the experiment had a philological dimension, it is because of my interest in pastiche, which in this case was nothing more, and nothing less, than an attempt to teach myself to speak a dead language, one that is already part of the history of photography: the are-bure-boke (grainy, blurry, and out-of-focus) language that would become emblematic of post-war Japanese photography.

It was by chance that, not long after I was finished, I came upon an article buried inside an old Mexican newspaper. It reported that El pecado de Oyuki had been hugely successful in Japan, and that after the final episode had aired, Ana Martín, the actress who played Oyuki, had been contacted by members of the “highest echelons” of Japanese society—including, it was rumored, Emperor Hirohito himself. They wanted to invite her to Tokyo, to congratulate her personally on her “flawless” portrayal of a Japanese geisha.